ÅOP is not good enough!

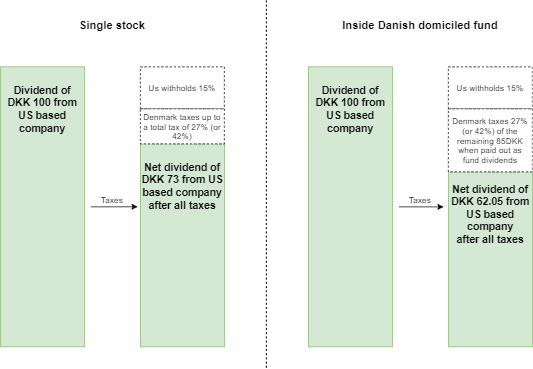

I had written a long paragraph, but I deleted it all cause the point is simple: ÅOP hides the fact that when buying index funds, you are taxed twice on most foreign dividends. To clarify through example:

- When you buy a classic “global” index it will typically hold ~50% US stock.

- When these stocks issue dividends (typically 2% per year) the US will withhold 15% dividend tax.

- When your index fund receives those dividends, it will then pay them out to you and you are then taxed 27% (or 42% depending on bracket) by the Danish tax authorities.

To contrast if you buy individual stocks then the process would be:

- When you buy a US stock and it pays a dividend the US will withhold 15% dividend tax.

- When you receive those dividends you only pay the remaining tax from the already paid 15% and up to 27% (or 42% again depending on bracket)

Given a typical 2% dividend the difference in efficiency is easily seen to be:

2%*85%*73%=1.241% paid out through an index fund

2%*73%=1.46% paid out through an individual stock

So even if the ÅOP is only ~0.40% for index funds then for funds tracking a US-based index, you could probably mentally add 0.2% to that and not be exaggerating. Of course, readers here probably won’t be buying just US funds. Danish stocks inside a Danish index fund won’t be subject to double taxation as the Danish tax authorities will not be charging “kildeskat” (withholding tax) on Danish dividends paid out to a Danish company. From what I gather (emails to fund managers) there seems to be a similar deal with Sweden where the Danish domiciled stock funds won’t pay kildeskat in Sweden but for lots of countries that tax will be 15% and upwards. Japan is 15% for sure (or it might be 15.3) and countries like Switzerland and Germany generally withhold a lot more than 15% for private investors so I guess even after applying and getting tax refunded they will still have this 15% extra taxation based on the applicable “dobbeltbeskatnings-overenskomst”. The agreements between Denmark and specific other countries can be found at the tax departments homepage here: dobbeltbeskatningsoverenskomster. But in general all but a few countries agree to some form of minimal allowable withholding tax with Denmark.

Index funds: further inefficiencies

Although there are plenty other inefficiencies in index funds the tax one is the one that stands out to me as something that really should be disclosed and probably should be part of ÅOP. In the following I’ll just very briefly touch on some other inefficiencies but for depth you can visit the Miranova link below or consult other sources.

Asset turnover: Most readers here are probably familiar with the phrases “buy and hold” or “time in the market” that are often considered part of any passive strategy. It can then seem strange that around 57%-77% of total fund holdings are sold each year according to Miranova (Analyse af skjulte omkostninger) and then of course a comparable amount rebought. This is for general Danish stock invest funds and thus might not be true for index funds specifically (I speculate it’s a lot lower but probably still meaningful). All these trades come with brokerage fees and according to Morningstar’s analysis (Analyse af kurtageniveauet i danske investeringsforeninger) these fees are surprisingly generally higher than what an informed private investor is paying when trading on Nordnet or Saxo. All this turnover can be necessary when a lot of people buy or sell shares in the investment fund or when the fund has to pay out dividends. Obviously when the fund receives dividends it can’t just have them lying around in cash for up to a year while waiting to pay them out to investors so they are invested and the fund must then sell of stocks to fund the dividend payouts at a later date. Outside of just the fees all these trades will generally incur losses to:

Spread which could be quite substantial when trading more than 100% of the total assets under management each year. Spread is the difference in bids and asks when trading stocks or other assets. Generally, the spreads will be low for liquid stocks like the top ones in most indexes but for large indexes they can get larger since the index is tracking smaller, less liquid stocks. The thing with spread is that it’s not an actual fee and thus won’t go into any ÅOP or similar fee declaration but will just reflect in slightly worse performance of the fund than the actual benchmark. Still most index funds beat the benchmark they are following according to their own graphs so how can that be – they don’t benchmark vs. the actual index but usually benchmark against the Net Return index which assumes a 30% withholding on dividends so if they only have a 15% withholding from major markets the spreads will still not push them across the 30% dividend withholding threshold for losing vs. the benchmark.

Forced realization: I think I’ve mentioned this in a previous post or at least in previous comments but all the generated turnover in the funds (necessary or not) means the funds will be realizing a lot of the gains in the stock market in up years and this realization inside the funds they are then forced to pay out as dividends. That can mean that in years where the global dividend yield for an index is around 2% the funds themselves might still be forced to pay out something like 8-12%. This dividend payout is then taxed which in practice imposes a notional gains tax on the fund investor since the total tax paid for the dividends can be higher than the actual growth in market value – as I’ve mentioned before this is the main reason I haven’t been holding funds in liquid assets so far.

Market impact: When big investment funds sell off or buy a large volume of a single stock they can actually drive the price up or down and thus get their shares at too high a price or sell their shares too cheaply. The Miranova analysis above estimates the effect at around 0.2% though I must say Miranova might be a bit biased in their analysis so the effect might be a bit lower than that. Again, this is not directly measurable so it is not part of ÅOP and like spreads can only be seen by comparing fund growth to the index it tracks.

Currency conversions: When trading stocks the funds need to do currency conversions since they are trading on a lot of markets. These conversions are usually done as 0 fee but with a buy sell spread and this means that like the bid-ask spreads the actual costs of currency conversions are not included n ÅOP.

Cash drag: This is minor but every fund will have some cash drag – that is to say they will have some amount of cash at any point from dividends by underlying stocks, from sales of stocks etc.

ÅOP holding period assumption: some sources will also say that a problem with ÅOP is that it is based on a 7-year holding period while most investors only hold for 5 years on average so the buy and sell fees are too low in ÅOP. I don’t think this is really an issue – most should be holding for longer than 5 years and on most funds the running costs, buying and selling fees are each specified visibly.

How does it translate to international ETF’s?

Withholding taxes exists for dividends between most countries. To touch this briefly; most investors looking to diversify will buy global funds and since those are usually ~50% US based stocks the main consideration is the agreement between USA and the country of domicile for the fund. A quick glance over dividend withholdings from USA seems to suggest that unless your fund is domiciled in Bulgaria, China, Japan, Mexico, Romania or Russia at least 15% will be withheld. For ETF’s another possible issue you could run into is that the dividends paid out by the ETF are then themselves subject to withholdings (that in the best case are then subtracted from your Danish tax burden), but my experience so far is that most Danes buy ETF’s domiciled in Ireland and as can be seen here Ireland does not withhold dividend taxes when paying dividends to Danish investors: Ireland Corporate Withholding Taxes.

A quick TL:DR:

For those that skipped the above or just want a short resume:

- There are various costs or inefficiencies when holding index fonds that are not part of ÅOP.

- A big one that often goes unnoticed is that dividends paid out from companies in another country than the fund domicile are often taxed doubly – first as withholding and then further when you receive your dividends in DKK. The effect might be around ~0.2% of total invested capital but can vary a lot depending on dividend payouts and countries in the fund.

- Other costs not shown in ÅOP are currency conversions and spreads and while market impact and cash drag can’t really be seen as costs, they also impact your return in the fund compared to the tracked benchmark.

- ETF’s or Danish domiciled index funds are still the cheapest way to get very large diversification – the choice between them is usually based on tax rather than exact costs.

This is an archived version of the site. Comments are no longer accepted.